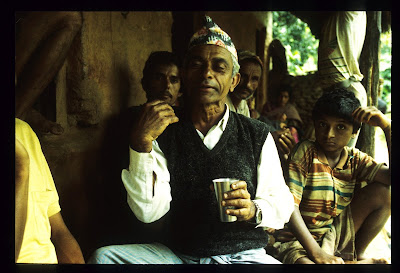

At the mention of the word "irresponsible" this man, one of the village elders joined the argument and began to upbraid the farmer who had brought the new plow up the mountain. He asked the farmer if he knew who made the plow. The farmer replied that he didn't know who made it?

At the mention of the word "irresponsible" this man, one of the village elders joined the argument and began to upbraid the farmer who had brought the new plow up the mountain. He asked the farmer if he knew who made the plow. The farmer replied that he didn't know who made it? The elder then asked him who in their region could repair the cast iron shoe if it cracked? The farmer said he did not know anyone who could fix it. The elder then asked the farmer if he felt like the new plow was more than marginally better than his older plow. And the farmer responded that he didn't know. He said he felt like the metal shoe would work better in the soils on the ridge but he had not been aware of how brittle the cast iron is and how easily the plow might break if it hit a ledge or a large rock hidden beneath the soil.

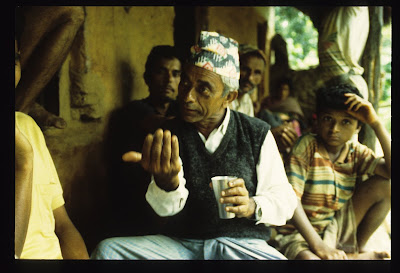

The elder then asked him who in their region could repair the cast iron shoe if it cracked? The farmer said he did not know anyone who could fix it. The elder then asked the farmer if he felt like the new plow was more than marginally better than his older plow. And the farmer responded that he didn't know. He said he felt like the metal shoe would work better in the soils on the ridge but he had not been aware of how brittle the cast iron is and how easily the plow might break if it hit a ledge or a large rock hidden beneath the soil. The elder expressed his opinion that this deal he had made was to benefit the company in India that makes the plows and the saleman who gave the farmer (now seen in the yellow shirt) the plow but the deal did not benefit the farmer in the least. He had had to carry it all the way up to the village and he would not be able to convince three other farmers to buy one of the plows so he was stuck with it.

The elder expressed his opinion that this deal he had made was to benefit the company in India that makes the plows and the saleman who gave the farmer (now seen in the yellow shirt) the plow but the deal did not benefit the farmer in the least. He had had to carry it all the way up to the village and he would not be able to convince three other farmers to buy one of the plows so he was stuck with it. I was impressed by the course of the discussion and the thoroughness of the investigation. It seemed to be a model of sustainability where sustainability was as much about technical facts and hard science as it was about human values.

I was impressed by the course of the discussion and the thoroughness of the investigation. It seemed to be a model of sustainability where sustainability was as much about technical facts and hard science as it was about human values.I was reminded of a speech by Garrett Hardin that he made in 1968 titled "The Tragedy of the Commons" that is, for all intents, a discourse on sustainability through the argument for imposed controls on population growth. In the speech Hardin states that one of the tragedies of the commons is that men, over time, are compelled to ruin the commons through greed and misuse. He uses an example of an early civilization where the commons is a pasture where village herdsmen can graze their cows. He observes that each herdsman will try and increase the number of cows so he can increase his profit but as he does so he will eventually destroy the pasture. This, Hardin concluded, is because no one is overseeing the commons. The commons, he says, are in the hands of the people who use them.

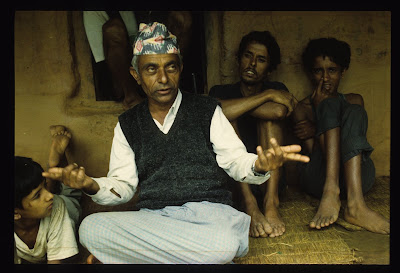

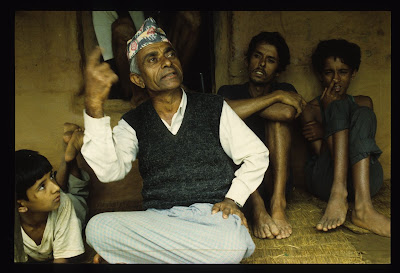

As I watched this elder discuss all the issues of the new plow versus the old plow I realized he was really talking about the commons and sustainability and he was the one overseeing the commons. He was legislating the commons based on the values instilled in him by ancient laws.

Where he touched on the commons was not so much about the plow and the system that is in place to sell the plow and how it creates an increase for the manufacturer and a decrease for the buyer, but on another example he used about a new water system that a contractor tried to sell the village a few years ago. The village's water is limited to a few springs because they are high up on a ridge. In the hot dry season of late summer the water decreases to a trickle and villagers must descend the mountain a few miles and carry water back up from a spring. The contractor thought the village would be ecstatic about a new water system which would pipe in water from many miles away through a plastic pipe. The elder explained all this to me as he waved his hands around and made these theatrical facial expressions.

Where he touched on the commons was not so much about the plow and the system that is in place to sell the plow and how it creates an increase for the manufacturer and a decrease for the buyer, but on another example he used about a new water system that a contractor tried to sell the village a few years ago. The village's water is limited to a few springs because they are high up on a ridge. In the hot dry season of late summer the water decreases to a trickle and villagers must descend the mountain a few miles and carry water back up from a spring. The contractor thought the village would be ecstatic about a new water system which would pipe in water from many miles away through a plastic pipe. The elder explained all this to me as he waved his hands around and made these theatrical facial expressions. In the end the village elders rejected the contractor's proposal because they found out there were a number of hidden costs to the project which eventually would have drained the village's money. They would end up paying for water by the gallon and they would also be responsible for repairing the water line if it broke. It was not a sustainable proposition, they thought and turned it down.

In the end the village elders rejected the contractor's proposal because they found out there were a number of hidden costs to the project which eventually would have drained the village's money. They would end up paying for water by the gallon and they would also be responsible for repairing the water line if it broke. It was not a sustainable proposition, they thought and turned it down.These are reasonable points in this discussion given that we were sitting in one of the most remote villages in the world. It was a discourse in sustainability. Hardin said a number of things in his now famous speech that were seminal and that should be reviewed often by anyone interested in sustainability, but he did miss one point: the commons were regulated and in most cases by the village elders. It has only been recently that the commons have been diminished.

No comments:

Post a Comment